|

|

Music education

“East-West” in the Music Education in Azerbaija

Author:

City

:

Baku

Country :

Azerbaijan

Pages

:

1

::

2

::

3

- “Do we Azerbaijani Turks, need to spend time, energy and means to study […] European music? Yes, we do and we should, because via studying European music we comprehend centuries-old music art that produced a number of great masters whose works cannot remain foreign to any nation that claims to be recognized as cultured one.” 1 This idea put forward by Uzeyir Hajibeyov in 1921 was followed by his claim to intensify “the scientific and artistic work in the field of folk music” that “would finally place Eastern music at the honorable place next to Western music […]”2 This concept has become programmatic for many generations of music educators in Azerbaijan.

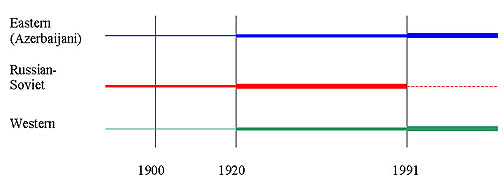

Three major components – Western, Eastern-Azerbaijani and Russian (after 1920 Russian-Soviet) in various proportions have determined the concept of music education in Azerbaijan in the 20th century: its mission, goals and objectives, contents and methodological approaches. The diagram below helps to grasp dynamics of these factors throughout the last century:

When in 1900, Antonina Yermolaeva, a young pianist graduated from the Tiflis Music College under the RMO (short for Russkoie Muzykalnoe Obshestvo: “Russian Music Society”) 3, established the first private music school in Baku, scarcely she realized that it would be a first stone to be laid in a foundation of a huge building. Remarkably, Azerbaijan happened to be the only Muslim province of the Russian Empire spanned with the RMO activities. After a year, this school obtained a status of the Music Classes under the RMO: an important change that increased financial support of the institution and allowed to hire high-skilled musicians from Moscow and Petersburg. Therefore, 9 October 1901 should be viewed as a date of establishing systematical music education of Western type in Azerbaijan. The String Quartet, and the Symphony Orchestra were founded under the school in 1906 and 1909 respectively; eventually their concerts attracted more audience gaining a status of remarkable events in the town. In November 1916, after having incorporated certain changes in curriculum and increased general requirements, the classes were reorganized as the Music College. However, the situation was not as promising as it may look at first glance. First, newly established institution targeted exclusively Russian-speaking part of population rather than natives: all faculty members were invited from Russia, and the only language of instruction was Russian. As Kovkab Safaraliyeva reported, first Azerbaijanis joined the RMO classes in 1908-1909; in 1912 their number reached 7, which still was only 5% of a total number of students. 4 Another serious obstacle was a high cost of study that determined rather elite character of this school.

The RMO Music Classes in Baku featured two components of the aforementioned triad. The education they provided was Western by nature, since the RMO itself exemplified the “Western” pole of Russian music. Russian part laid on a surface: all instructors and, correspondingly, teaching methodologies represented Moscow and Petersburg music pedagogy. As for Eastern part, it was equal to zero, which was expected: the RMO Baku classes were purely “imported product” and functioned in the country staying at the very early stage of art music tradition.

As for Eastern factor – it had developed in the music education in Azerbaijan in centuries-old form of music majlis. Music majlis, a public gathering of musicians, poets and art lovers resembled that in European music salons and was usually held in private houses. Majlis participants shared mastery of performing traditional music and reciting poetry; as such, majlises combined creative and educational purposes serving as an effective instrument of passing knowledge of mugham and other forms of traditional music from accomplished masters to younger generations. Since the 12th century, majlis tradition has been developed in Azerbaijan’s many cities, however, those in Baku, Shamakhi and Karabakh were particularly noteworthy. Those who ever traveled over Azerbaijan, were impressed with this form of collective creativity – such as Alexander Dumas, a famous French writer who attended majlises in Shamakhi and Shusha in 1858, and met with Natavan, ruler of Karabakh and poetess leading Majlisi-Uns. 5

Thus, Azerbaijan stepped over a threshold of the 20th century possessing the two parallel concepts of music education: traditional Eastern and modern Western, the latter applied via Russian model. They simply co-existed without either crossing or influencing each other. The question evolves: if the social and political status of Azerbaijan had not changed so catastrophically in 1920, would such a dual concept of education have ever continued to exist? Most likely, the synthesis of the East and the West would have inevitably occurred in the field of education, since the ideas of blending “two planets” had already emerged in Azerbaijani culture. Yet, the process would have never been such intense as it happened to be; neither gains nor losses would have been so detectable and distinctive from the non-Soviet rest of the Muslim region.

1. Uzeyir Hajibeyov, “Muzykal’no-prosvetitel’nye zadachi v Azerbaidzhane” (Music enlightening tasks in Azerbaijan) Iskusstvo, no.1, 1921, 10-11.

2. Uzeyir Hajibeyov, “O muzykal’nom iskusstve Azerbaidzhana” (About musical art of Azerbaijan) (Baku: Azerneshr, 1966), 26.

3. Russian Music Society (RMO) was founded in 1859 in Petersburg on an initiative of a composer, pianist and conductor Anton Rubinshtein and under a patronage of the Russian Emperor family. It had an enlightening mission conducting concerts, competitions and festivals in many regions of the Russian Empire. Many prominent Russian composers, including Piotr Tchaikovski, Sergei Taneev and Milii Balakirev were involved in the RMO’s activities. Russia’s two major schools of music – Moscow and Petersburg conservatories were created under an umbrella of the RMO. In a short period of time 27 branches were established throughout the Russian Empire, including those in Kiev (1863), Kazan’ (1864), Khar’kov (1871), Nijni Novgorod (1873), Tbilisi (1883) and Odessa (1884).

4. Kovkab Safaraliyeva, “Muzykal’noe obrazovanie v Azerbaidzhane” (Music education in Azerbaijan) Azerbaidzhanskaia muzyka (Azerbaijani Music) (Baku: Gosmuzgiz, 1961), 278.

5. Alexander Dumas was impressed with Natavan’s personality that obviously contradicted cliché expectations about Muslim woman: she possessed encyclopedic knowledge of history and literature, spoke several European languages and was known as an accomplished chess player. On the memory of their meeting, French writer presented Natavan chess set, now preserved at the Museum of Azerbaijani Literature in Baku. Later Dumas and Natavan maintained friendly relations as depicted in their correspondence and Dumas’ book Adventure in Caucasia (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1962)

Pages

:

1

::

2

::

3

|